Inclusive Volunteering

Toolkit

Navigation

V.2

Updated January 2025

This toolkit and report are the result of a project in 2022/23 supported by the Scottish Government as part of Scotland’s Volunteering Action Plan.Make Your Mark is an ongoing campaign to make heritage volunteering for all in Scotland. It was created in 2020 as part of Our Place in Time, Scotland’s first national strategy for the historic environment.Download a PDF version of the toolkit and a PDF version of the report.

The team behind this toolkit

Yvette Taylor is a Professor in the School of Education, University of Strathclyde researching gender inequalities, LGBTQ+ life and social class. Yvette holds a Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) Personal Fellowship (2023-25) on Queer Social Justice.Churnjeet Mahn is a Professor in the School of Humanities, University of Strathclyde researching migrant communities and LGBTQ+ life. She has worked on Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) initiatives in the Scottish heritage sector.Erin Burke is the Campaign Coordinator of the Make Your Mark campaign. They have a background in community engagement and inclusive heritage practice.Jeff Sanders is the Project Manager for Dig It! at the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. He holds a doctorate in archaeology and his professional experience focuses on engaging new audiences with heritage.

Additional Thanks

Graphic Design, Website, Accessibility. Brian Tyrrell, Stout Stoat Press.

Illustrations and Photographs. Saffron Russell, Julie Howden, and Helen Pugh. Thanks to Archaeology Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland, Scottish Civic Trust, David Livingstone Birthplace, Glasgow Women’s Library for additional photos.

First Published 2023. Updated 2025.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit:

creativecommons.org.

produced in partnership with

Contents:

Inclusive Volunteering Toolkit

All links lead to content on this website.

8a. Process

About This Toolkit

This toolkit is designed to support voluntary organisations in Scotland to make their volunteering programmes more inclusive.

Background

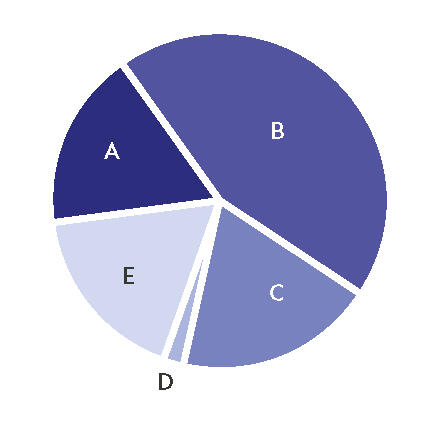

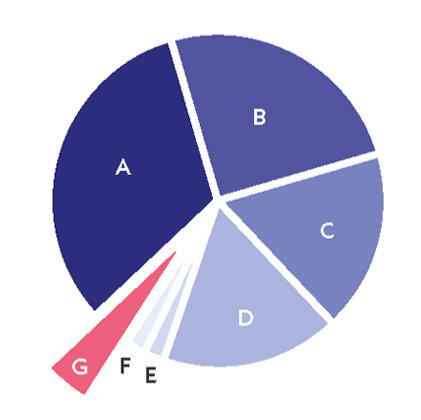

This toolkit is the result of a project in 2022/23 supported by the Scottish Government as part of Scotland’s Volunteering Action Plan. Further information on the research that informed this toolkit is available for download in a full project report.Conducted across 2022-23, the project aimed to investigate the accessibility and inclusivity of volunteering in Scotland, and how barriers to volunteering could be removed.The toolkit has been designed in response to data generated by a survey of Make Your Mark members (52 respondents from a variety of large, medium and small volunteer-involving organisations across Scotland) and 4 focus groups composed of volunteers and people interested in volunteering.The survey focused on attitudes and approaches to different aspects of diversity and inclusion in volunteering, especially how positive change can be measured.The focus groups gathered the views of a diverse range of participants which highlighted barriers and opportunities for migrant, asylum-seeking, refugee, and BAME communities, disabled people, and people in formal education. Collectively, the groups also highlighted barriers for LGBTQ+ volunteers, older volunteers and issues related to social class1.Drawing on this data, and the existing experience of the Make Your Mark membership in the form of case studies, the toolkit offers practical steps to enhancing inclusion and diversity in the volunteering sector in Scotland.This toolkit is regularly updated to reflect changes in best practice and highlight new case studies and resources about inclusive volunteering. It was most recently updated in January 2025.

1. For definitions of key terms, please see the glossary at the end of this toolkit.

Illustration Credit: Saffron Russell.

How to use this toolkit

This toolkit includes information and guidance on inclusive volunteering, as well as a series of reflective exercises and challenge-framed questions.

It is recommended that all readers begin with reviewing and completing the reflective exercises within sections 1 and 2 to establish an understanding of the current voluntary sector in Scotland and barriers to volunteering. Readers should then complete section 3, which will help them reflect on inclusion individually and within their own organisation.

This is a reflective exercise

These exercises and questions are designed to be undertaken by small groups (3-5 people) combining staff at volunteer organisations (or volunteer coordinators) and volunteers.Subject to capacity, they can also be used by individuals to reflect on their own practices and challenge their thinking.

Readers can then proceed through the rest of the sections chronologically, or have the option to choose which topics within sections 4 through 6 are applicable to their organisation’s volunteering challenges and priorities. This flexible approach to the toolkit recognises that each organisation will be at different stages towards building an inclusive volunteering programme, and have different staffing, structures and budgets for volunteering.

It is then recommended that all readers end with reviewing section 7, and incorporating their learnings from the toolkit into an inclusive volunteering plan for their organisation.

Within each section of the toolkit, further reading and case studies are provided for those interested in specific topics.

An appendix with a glossary and template equalities monitoring form can be referenced at the end of this document.

1. Defining volunteering

What is volunteering?

The Scottish Government’s national Volunteering for All framework defines volunteering as:

"a choice. A choice to give time or energy, a choice undertaken of one’s own free will and a choice not motivated for financial gain or for a wage or salary… it is used to describe the wide range of ways in which people help out, get involved, volunteer and participate in their communities (both communities of interest and communities of place)."

Generally, a definition of volunteering has three components:

1. The activity benefits people outside your immediate family.

2. The activity is unpaid.

3. A person actively and freely chooses to undertake the activity.

Volunteering is commonly divided into formal and informal volunteering. Formal volunteering is when people volunteer through an organisation or group, such as public sector bodies, community councils, local clubs, charities, etc. With formal volunteering, there are usually agreed roles, responsibilities and management arrangements. Informal volunteering occurs on a person-to-person level that is unmediated by a third party organisation, such as helping out a neighbour.

Photo Credit: Historic Environment Scotland.

Volunteering versus placements versus unpaid work

Volunteering is not the same as student placements or unpaid work. Knowing the difference between these ensures that your organisation inclusively and effectively engages volunteers, as well as ensures that your organisation does not violate UK employment law.Student placements are ways for students to gain practical experience as part of an education or training course. It involves a student spending a set amount of time with an organisation to gain experience and fulfill course requirements. There is often a placement contract that sets out expectations for the student, as well as highlights set learning objectives. The student’s performance is assessed by their course leader with input from a designated staff member at the organisation, and in many cases requires the student to complete a project or paper reflecting on their experience. Because a placement is part of coursework required for a qualification, it is not undertaken by choice and is not volunteering. Volunteer Wiki provides more information on the difference between volunteering and internships.When a person volunteers they are choosing to undertake an activity that is unpaid, but volunteering is not unpaid work. According to the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP), unpaid work is undertaking a role that would normally be paid within the private or profit-making sector. Choosing not to get paid for a role that would normally be paid is not volunteering, and the money that a person would normally have been paid for this work may be counted as a person’s earnings.

Volunteer Charter

Volunteer Scotland’s Volunteer Charter is a tool that you can use to underpin good relations within a volunteering environment. It outlines 10 key principles for assuring legitimacy and preventing exploitation of workers and volunteers.Are your volunteer roles in line with the Volunteer Charter? If your organisation is falling short of any of the 10 key principles, what steps can you take to address this? Is your organisation ready to become a Charter Champion?If you’re looking to delve deeper into how your organisation can incorporate the Volunteer Charter into your practices and policies, Open University and Volunteer Scotland have developed a free online course about applying the Volunteer Charter within your organisation.

2. Volunteering in Scotland: Where Are We Now?

Volunteering is a central part of civic life and is most commonly motivated by a desire to make a social contribution or to participate in networks that can enhance a sense of belonging and purpose. This section of the toolkit reviews current data on inclusive volunteering in Scotland.

COVID-19 and the cost of living crisis are two recent examples of forces that have had a negative impact on third sector finances, but which have also underlined the importance of the third sector, especially volunteering, in ensuring the sustainability of public life and services across communities (Scottish Third Sector Tracker, 2024).

The Scottish Government’s Scottish Household Survey (2023) found that:

18% of adults took part in formal volunteering in February 2023 to February 2024. This is four percentage points lower than the 2022 figure (22%) and eight percentage points lower than pre-pandemic levels (26%). Volunteer Scotland’s report on the 2023 SHS results has attributed the decline in formal volunteering to the cost of living crisis and the pressure this puts on people’s time and ability to make a living.

Female formal participation rates remain higher than males (20% vs 17% respectively).

Disabled adults were less likely to volunteer than non-disabled adults (16% versus 19%). However, volunteer participation rates decreased more for people without a disability than for people living with a disability (a decrease of four percentage points compared to only one).

Adults aged 35-59 have the highest formal volunteer participation rates of 20%. Younger adults in Scotland (aged 16-34) have the lowest formal volunteer participation rates for the second consecutive year (16%).

The ethnic group with the highest volunteer participation rate is ‘white-other British’ (27%). Adults in the ‘minority ethnic’ group have a participation rate of 22%. The volunteer participation rate for white Scottish adults is 21%.

People living in the 20% least deprived areas of Scotland are more likely to volunteer than those from the 20% most deprived areas (24% versus 12%). However, the gap has decreased by two percentage points from 2022 and five percentage points from 2019.

Those living in rural areas have a higher volunteering participation rate (23%) compared to the rest of Scotland (17%).

Photo Credit: Glasgow Women’s Library.

Volunteer Scotland’s Report on Volunteering Trends in Scotland (2022) has shown that in Scotland you are more likely to volunteer if you are:

Female

Non-disabled

Aged 35 to 59

White

Living in the least deprived areas of Scotland

Retired

Living in a rural area

This toolkit is designed to help volunteer organisations think about how to distribute the value, opportunities and benefits of volunteering across the whole of Scottish society.

Inclusive volunteering in Scotland

Does this data surprise you or not? Discuss your responses.Have there been changes to who volunteers and why over the past 3-5 years in your organisation? If so, why do you think this has happened?Do you think everyone in society should have equal opportunities to volunteer or is it better suited for particular groups of people? Discuss why.What’s the data or information about volunteering that you’d like to know but don’t have (e.g. average hours of volunteering, or number of disabled volunteers)?

What is Equality, Diversity and Inclusion?

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) has provided a framework for many organisations to address cultures of inequalities. One frequent criticism of EDI policies is that they can encourage a culture of ‘box ticking’ where there are token changes without challenging underpinning norms in an organisation.In this toolkit, we define:

Diversity as attributes which reflect the make-up of society (e.g. race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, disability, faith, etc).

Inclusion as a values-driven practice to create a diverse, open and welcoming environment which is evidenced through concrete commitments and action.

The Equality, Inclusion and Human Rights Directorate at the Scottish Government identifies priority areas for inclusion work, which covers, and goes beyond, protected characteristics.

Case Study:

Creating an Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Policy

Glasgow Women’s Library has developed an Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Policy to ensure that in carrying out its activities, the organisation will have due regard to promoting equality of opportunity, diversity and inclusion across the organisation, promoting good relations between people of diverse backgrounds, and eliminating unlawful discrimination.

Photo Credit: Julie Howden.

Why is inclusion a particular issue for the voluntary sector?

Volunteering is a key way to develop new social networks and skills which can help with employment. The value of volunteering is most likely to have a transformational social and economic impact on individuals and communities which experience marginalisation. However, these individuals and communities are also more likely to experience:

Financial barriers to participating in volunteering (from childcare to requirements for paid work).

Information barriers to learning about volunteering (from language to regular venues for advertising opportunities).

Social and cultural barriers to volunteering (from a lack of diversity amongst existing staff and volunteers to imposter syndrome).

Access barriers to participating in volunteering (from access to screen readers to a willingness to support disabled volunteers).

Key reasons inclusion initiatives fail or have limited success include:

Narrow and limited applications of diversity initiatives which lack ambition and do not effect long-term change (e.g. isolated recruitment of volunteers who count as ‘diverse’ without any dedicated support for the individuals).

A resistance to acknowledging inequalities in organisational culture(e.g. tackling entrenched inequalities relating to gender, disability or race).

A lack of resources, skills or knowledge (e.g. organisations expressing a lack of confidence to address equality issues).

A commitment to inclusive volunteering involves taking meaningful action to create equal and diverse access to the personal, social and economic benefits of volunteering. This toolkit has links to a range of resources and expertise in the sector; you are not alone!Make Your Mark also continues to offer dedicated support, especially in fostering smaller communities of practice.

It’s important to recognise that there are a range of organisations working on developing inclusive volunteering opportunities. Challenges include:

Financial resources and capacity to deliver inclusion-focused initiatives, especially for smaller organisations.

Worries about ‘language’ or terminology and ‘getting things wrong’ with inclusion work.

Not knowing where to start, or how to know inclusion initiatives are working.

Inclusion in the voluntary sector

What are the most important values in your organisation?

Are you surprised by any of the categories on the Equality, Inclusion and Human Rights Directorate’s list of priority areas for inclusion?

How do you promote a culture of inclusion? What works best in practice? What do you think needs more work?

What are the challenges and opportunities for doing diversity and inclusion work in smaller versus larger organisations? Is it easier to change a culture in a smaller organisation or a big one?

3. Understanding Barriers to Volunteering

Potential volunteers may face various barriers that could dissuade or prevent them from volunteering. This section of the toolkit identifies possible barriers to volunteering, including economic, social, cultural and physical barriers.

Economic barriers

to participation

Economic barriers to volunteering are becoming more prevalent due to the cost of living crisis. Volunteer Scotland’s quarterly Cost of Living bulletins track the impact of the crisis on volunteering, with many voluntary organisations experiencing increased demand, rising costs and stagnating income, decreasing their capacity to involve volunteers. Prospective and current volunteers also have less time and money, which has negatively impacted many people’s mental health, decreasing people’s capacity to volunteer.In this economic context, it becomes more critical for organisations to include a substantial budget for inclusively engaging volunteers within funding bids. More information about how to do so and what sorts of costs to consider can be found in section 6.

Examining barriers

Potential volunteers may face some of the following economic barriers to volunteering with your organisation:

Childcare costs

Some volunteers may have childcare responsibilities, and need to pay for childcare cover whilst they volunteer.

Reflective exercise: What practical support can your organisation provide to support volunteers with childcare costs? If this is limited, how could it be fairly allocated? If it’s not available, are there other flexible opportunities for volunteering? Is it possible to learn from best practice in the past or from other organisations?

Time

All volunteer roles require people to give their time, but some people may need to work long hours to make ends meet, have childcare or other responsibilities, and thus have a lack of free time.

Reflective exercise: What is the future potential for flexible volunteering opportunities?

Travel expenses

Some volunteer roles are in-person rather than online. Some volunteers will have to access transport, which can be prohibitively expensive.

Reflective exercise: What practical support can your organisation provide to support volunteers with transport costs? If this is limited, how could it be fairly allocated? If it’s not available, are there other flexible opportunities for volunteering?

Equipment costs

Some roles require equipment (computers, wifi, uniforms, tools) to be undertaken.

Reflective exercise: Is there a way of supporting access to equipment through pooling resources with other organisations or having an equipment bank? How could this information be made available to potential volunteers?

Disclosure costs

Some roles require disclosure checks, which cost money and may discourage people with convictions or experiences of being unhoused from applying to volunteer.

Reflective exercise: Can you use Volunteer Scotland’s free Disclosure Services? If not, Is there an annual budget to support disclosure costs? How could this be fairly allocated to potential volunteers?

Benefits & Rights to Work

Some people who receive UK State benefits or who are seeking asylum may not be aware that volunteering will not affect their benefits or status, and may be nervous about volunteering.

Reflective exercise: Do you have the knowledge and skills in your organisation to offer basic information or signposting to support anyone in this position?

Food & drink

Some people who volunteer may be giving up time that they’d otherwise use to earn money to pay for food and other needs.

Reflective exercise: Are there forms of material support (e.g. community and team building meals) that could be developed at your organisation?

Social & cultural

barriers to belonging

Although volunteer programmes may encourage everyone to apply, attitudes, assumptions and previous experiences may prevent people from getting involved. Each sector of volunteering has some common assumptions about what a typical volunteer looks like.

For example: There is a perception that museum volunteers are typically white and middle-class, and that many have degrees or qualifications. Some potential volunteers may think that it would be difficult for someone without qualifications or a good knowledge of history to volunteer in a museum.

Challenge: To what extent do you think this perception of museum volunteers is true? Who is considered the ‘typical volunteer’ within your sector or organisation?

Examining barriers

Potential volunteers may face these social and cultural barriers to volunteering with your organisation:

Experiences of structural discrimination: Experiences of racism, for example, can reduce faith in the willingness of white-led or white dominated organisations to support and value diversity.

Case study: Recognising racism in volunteer engagement. The Black Lives Matter Protests of 2020 renewed calls for racial justice and systemic change. In this case study on recognising racism in volunteer engagement, Faiza Venzant, Executive Director of the Council for Certification in Volunteer Administration, identifies and dismantles the structures, policies and processes that are built upon white supremacy culture.

Lack of confidence: Everyone has useful and valuable skills and experiences, but some people may have had negative experiences where they were made to feel undervalued or unqualified in society. This is commonly experienced by marginalised groups (e.g. because of their disability or race).

Ideas about what ‘volunteering’ means: Many communities have informal types of voluntary work (e.g. religious service or ‘helping neighbours out’). This is very common in working-class, migrant, disabled and LGBTQ+ communities.

Reflective exercise: Is there anything volunteer organisations can learn from these informal volunteering models and vice versa?

Attitudes and assumptions amongst staff in volunteer organisations: The lack of diversity within volunteer organisations can lead to gaps in knowledge and lived experience, resulting in stereotypes and discriminatory views going unchallenged.

Reflective exercise: If you have tried to diversify the profile of volunteers in your organisation, has it worked? If you haven’t tried an inclusion and diversity initiative, are there 1-2 things your organisation could do differently to help remove barriers to participation?

Photo Credit: Helen Pugh.

Physical barriers to access

The site or building that people volunteer at can be a barrier to volunteering. There can also be physical barriers preventing volunteers from getting on-site.

Transport: The accessibility or availability of public transport links can make it difficult for some volunteers to get on-site to volunteer. This is especially true in rural areas.

Exterior elements: Physical barriers can prohibit people from entering your site, and may include things like parking areas, kerbs, paving, steps and doors.

Interior elements: Physical barriers can also prohibit people from moving around your site, having their basic needs met or engaging with the volunteer role. This includes things like stairways, doors, toilets and washing facilities, lighting and ventilation, lifts and escalators, floor coverings and signs.

Case study: Rural volunteering. The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland has recently opened several new facilities at their Highland Wildlife Park. As part of the redevelopment project, they’re also developing a new and improved volunteer programme in the heart of the Cairngorms. In this case study on rural volunteering, they share their successes as well as lessons learnt.

Reflective exercise: What elements of your site could you alter to increase accessibility? If you don’t have the budget to change all inaccessible elements, how do you prioritise what to change first? If you can’t alter certain elements of your site because of planning or structural restrictions, can you offer adapted roles that can be completed online or elsewhere?

4. Reflection on Inclusion in Volunteering Organisations

Each individual and organisation will be at different stages in developing awareness about equality, diversity and inclusion. This section of the toolkit will help you reflect on your own experiences and your organisation’s practices to identify areas for growth.

Reflecting on your own experiences

Everyone has different backgrounds, identities and needs that shape our position in and understanding of the world. It can be helpful to think through your experiences and how they impact you. There are several self-guided tools that can help:

The Privilege Walk helps people to become aware of the various privileges they might possess.

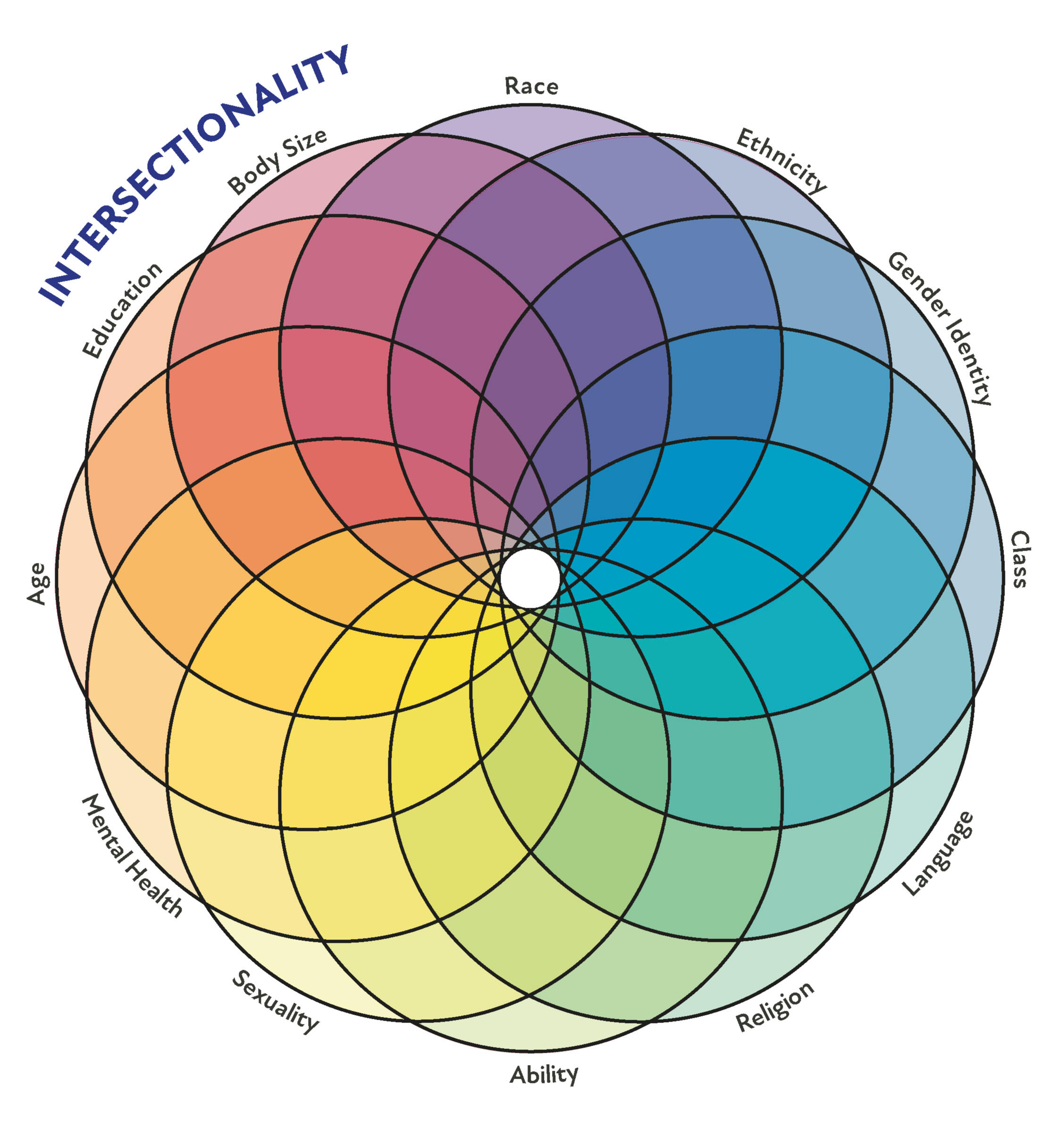

The Intersectionality Wheel helps people to visualise how various privileges interact and compound.

Power and privilege are two interconnected terms. They have become useful ways to conceptualise the everyday hurdles some people face when navigating daily life.For more guidance on terms related to equality, diversity and inclusion, please see the glossary at the end of this toolkit.

Privilege walk

What are the different kinds of power and privilege in your group? Are they the same? Different? Can you discuss how they shape your experience and viewpoints?

The Intersectionality Wheel is reproduced from designs by Sylvia Duckworth.

“Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it locks and intersects. it is the acknowledgement that everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and privilege.” - Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Expanding intersectionality

What other forms of power can you think of that impact members of your community?

Where is your organisation in the inclusion journey?

1. Groundwork

Does your organisation have the necessary skills and knowledge to implement NCVO’s recommendations for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion? Does your organisation collect data about the current diversity of volunteers?

2. Induction

Do your induction processes contain information that signposts support for diverse communities of volunteers?

3. Listening

Do volunteers feel that their views and voices are equally valued? Is there a culture where volunteers can report problems and have confidence in concerns being addressed?

4. Supporting

Are a range of mechanisms in place to acknowledge different volunteers need different kinds of support?

5. Reflection

Is there space to critically think with volunteers about what could be done differently or better?

6. Acting

Is a clear inclusive volunteering plan in place to address any issues relating to wellbeing, safety and/or discrimination? Have they been tested or used? Have they been proven to work well?

7. Learning

Can you document and record areas of best practice and learning to share with other voluntary organisations?

8. Evaluation

Do you combine qualitative and quantitative mechanisms to evaluate success?

Inclusive volunteering at your organisation

Based on your answers to this exercise, how would you rate where your organisation is in its inclusion journey from from 1-8 (where 1 is not started and 8 is highly developed)?

What areas do you need to work on?

5. Governance and Policies

The work of inclusion can too easily focus on siloing diversity into a problem for one part or department of the organisation, such as outreach, education or community engagement. Having expertise in inclusive governance and policies can be an important step forward in bolder, all-organisational approaches to equality and representing the society we live in. This section of the toolkit gives advice for inclusive governance policies and practices.

Leadership

To be truly transformative, inclusive policies and practices should be embedded in an organisation’s leadership. The most effective boards have a diversity of individuals with varying backgrounds and experiences, which ensures that issues are debated and understood from varying points of view.

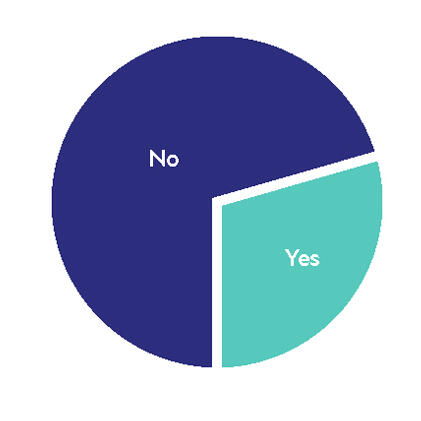

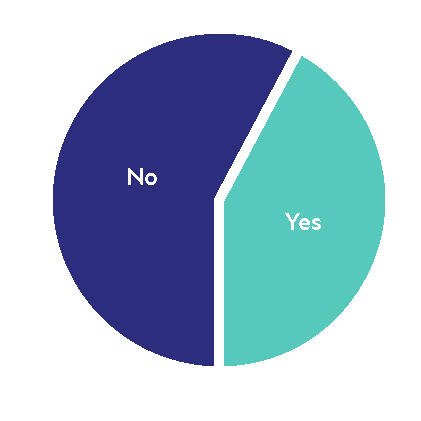

Despite this, the Charities Inclusive Governance Report (2022) found that:

“The UK’s largest 500 charities’ senior leadership teams and boards remain unrepresentative of the people they serve and employ.”

Only 13% of charity boards had gender parity, and 29% of boards were all-white. For boards of organisations on the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 Index, which are companies in with the highest market capitalisation, only 4% had all-white boards, demonstrating the market power of board diversification.

Getting On Board’s Practical Guide to Diversifying Boards takes you through the steps of how to approach the subject of changing your board composition with your existing trustees and chair. For further guidance, you can access Open University and Volunteer Scotland’s free online course about how to develop leadership practices within voluntary organisations.

Inclusive governance

Are the most senior/influential leadership teams in the organisation diverse?

Is there a commitment to diversity amongst the senior/influential leadership teams? If so, how is this demonstrated in action? Please think of 2-3 examples and how they work in practice.

Case study: Amplifying the voices of refugees and asylum seekers in decision making.

Involving refugees and people seeking asylum on boards can be mutually beneficial for the organisation and volunteers. In this case study on supporting refugees and asylum seekers to join boards, the Mental Health Foundation talks about how their Elevate and Beyond Visibility programmes have empowered and supported refugees and asylum seekers to join boards.

Policies for volunteers

While many organisations have policies that help protect and support employees, they do not always have policies to protect and support volunteers.Consider the use of the following policies and processes for volunteers:

Equal opportunities statement: NCVO has developed a template equal opportunities statement for voluntary organisations in the UK.

Volunteer agreement: Volunteer Scotland has developed a template volunteer agreement, which makes it clear what the volunteer can expect from the organisation and what, in turn, the organisation expects from the volunteer.

Volunteer policy: Volunteer Scotland has developed a template volunteer policy, which outlines clearly to all staff, volunteers and audiences why volunteering is needed.

Grievance / complaint process: Volunteer Scotland provides guidance on managing challenging situations with volunteers.

Feedback and evaluation processes: Volunteer Scotland provides guidance on measuring the impact of volunteering.

Inclusive volunteering policies

Is your organisation confident it could support diverse volunteers through these policies?

Example: A volunteer experiences a racist incident involving another volunteer. They have raised an informal grievance with their organisational contact, but do not want to make it official as they are afraid of what might happen next and feel traumatised by the incident.

What would your organisation do in this instance?

6. Inclusive Volunteering Steps to Positive Action

Volunteer organisers can take a variety of steps to develop meaningful and accessible volunteering opportunities for everyone. This section of the toolkit gives an overview of how to remove barriers to volunteering. The final topic of this section is an inclusive volunteering checklist that you can use to assess what facilities and services you can offer to be more inclusive.

Centring the voices and

experiences of volunteers in Scotland

Centring a diverse volunteer voice in the development of volunteer policies, procedures and opportunities is key to ensuring that your volunteer programme is accessible, inclusive, relevant and fulfilling for everyone.

Surveys

You could partner with a community group to survey their members about their perceptions and experiences of your organisation and volunteer programme.You could ask:

Have you heard of our organisation? If so, where/how?

Have you visited our site or participated in our events? Why or why not?

Did you know you could volunteer with us?

Have you considered volunteering with us before? Why or why not?

What would you want to get out of volunteering with us?

How could we make our organisation and volunteer roles more accessible, relevant or interesting to you?

Photo Credit: Archaeology Scotland

Focus groups

Another method you could use to better understand marginalised people’s perceptions and experiences of your organisation and volunteer programme is to host focus groups.

Our top tips for organising focus groups are:

Partner with organisations that engage with marginalised audiences. These organisations are best placed to understand their audiences’ needs, help you organise an accessible space and advertise the session to participants.

Ensure that you have everyone’s informed consent. Adapt NCVO’s template consent form to draft a basic consent form outlining the purpose of the focus group.

Frame the approach as an open discussion. Some focus group participants may be worried about offending a representative from your organisation. Be clear that the session is an open discussion, every experience is valid and there are no wrong answers. You could also consider hiring an external facilitator or partnering with a local equality council to help facilitate the sessions.

Establish caretaking practices and procedures. Some participants may talk about distressing instances of racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism and/or classism that they experienced whilst trying to visit a site or participate in a volunteer opportunity. Prepare a list of organisations and resources that participants can access for additional support should they need it. You should also make it clear to participants that they can take a break or leave at any time, and do not have to answer any questions they don’t want to.

Illustration Credit: Saffron Russell

Recruiting volunteers

There are several examples of inclusive recruitment best practice that the volunteer sector can draw on, such as:

The following information provides suggestions based on feedback from focus groups with potential volunteers from diverse backgrounds.

Sharing volunteer stories

Having your current volunteers share their stories can encourage people to try out volunteering by giving more information about roles and the benefits of volunteering. Content created by volunteers, also called user-generated content, is 10 times more trusted than content produced by organisations themselves, so it’s a powerful marketing tool.

You could share blog posts or videos with your volunteers talking about:

1. Their role and the tasks they undertake.

2. Why they were interested in volunteering.

3. Their favourite volunteering experience.

4. How volunteering has impacted their life.

Case study:

Sharing volunteer stories

Make Your Mark shares blogs and videos of heritage volunteers detailing their experiences of volunteering and why they love to volunteer.

Taster sessions

Taster sessions are informal ways for people to learn more about an organisation or volunteer role ahead of applying. They can help to alleviate any questions or concerns that people may have about volunteering.

During the session, it can be helpful to introduce the day by covering:

What your organisation does.

The benefits of volunteering.

What volunteer roles are available.

Any questions that volunteers may have.

People could then choose the role most interesting to them and break into groups to complete a small task associated with the role. After 20 minutes, groups could switch roles so people can try out a few different types of tasks and see what they like.

Shadowing opportunities, like taster sessions, can help potential volunteers get a sense of your organisation and volunteer roles, as well as alleviate any anxieties about volunteering.

Multiple ways to apply

Providing multiple ways to apply to your volunteer opportunities allows people to choose the communication channel accessible or most comfortable to them.

Multiple ways to apply could include:

Emailing a short paragraph about themselves and why they’re interested in the role.

Creating a short video about themselves and why they’re interested in the role.

Arranging a call with the volunteer organiser to have an informal chat about their interest in the role.

Attending a taster session before applying.

Case study:

Inclusively recruiting volunteers

In 2019 and 2020, Historic Environment Scotland reviewed their recruitment processes to make them more inclusive and easy to engage with. In this case study on inclusively recruiting volunteers, read about how they stopped asking for written applications, offered taster sessions, stopped asking for references and more.

Advertising opportunities

Advertising opportunities is a key issue. Developing a proactive plan combining social media (especially targeted at community groups), community radio stations and hubs and events within community settings is a positive step towards reaching ‘out’ to volunteers.

Working in partnership with community organisations is another beneficial vehicle for building trust, especially in resolving issues which may arise later. In your introductory communication to potential partners, you should specify:

1. What your organisation does.

2. What volunteer roles you offer.

3. Why you want to involve a more diverse range of volunteers.

4. What your volunteer programme can offer their members/audiences.

5. What the other organisation could do to support your volunteer programme. This might entail:

5a. Promoting your volunteer opportunities to their members / audiences.

5b. Distributing a survey about your volunteer programme to their members / audiences.

5c. Organising a focus group about your volunteer programme with their members / audiences.

5d. Organising an info session with their members, where you can meet them in a space comfortable to them and give information about your organisation and volunteer programmes.

5e. Their members / audiences visiting your venue and providing feedback on accessibility and inclusion

5f. Their members / audiences providing feedback on policies or role descriptions.

5g. Their members / audiences participating in a volunteer taster sessions to introduce them to volunteering with you and/or to give you feedback on how to be more accessible or inclusive.

Working with community collectives can help to connect volunteering organisations to other socially-driven care groups. Thistles and Dandelions have created a toolkit to help organisations partner with community groups.

If you’re keen to connect with a relevant partner organisation or group, but not sure where to start, Make Your Mark manages a database of organisations in Scotland who work with and represent excluded groups.

Case Study:

Partnering with local groups

To diversify their volunteer programme, the National Galleries of Scotland reached out to local charities and community groups that worked with excluded audiences.

In this case study on partnering with local groups to increase diversity, read about how they approached groups and adapted their opportunities to be more inclusive.

Photo Credit: Helen Pugh.

Flexible opportunities

Especially since COVID-19 and the cost of living crisis, flexible opportunities are a requirement for many people who can’t afford transport or childcare costs involved in volunteering, or have barriers related to health and/or disability. Ongoing innovation in sourcing flexible opportunities will allow more people to consistently engage with the benefit of volunteering.

Asking about volunteers’ needs

Having an open and ongoing conversation about volunteers’ needs is key to making volunteering more accessible. It’s important to avoid making assumptions and speak to each person individually about their needs, as every person has different abilities and has had different experiences.

To foster a culture of open conversation around needs, you could:

Provide detailed accessibility information on all volunteer role descriptions.

Ask volunteers at the application stage if they have any access needs that you should be aware of.

Organise monthly or quarterly catch ups with volunteers to check in and revisit how you can better support them.

Case study: Enabling everyone

to take action for nature

NatureScot supports people from a range of backgrounds to participate in the Scottish Invasive Species Initiative.

In this case study on enabling everyone to take action for nature, read about how they don’t require volunteers to have prior experience, provide free training and offer a range of flexible ways for people to get involved.

Offering adaptations

Once you’ve had a conversation with a volunteer about their needs and circumstances, have a think about how you could change up your practices to support their volunteering. You could:

Reconsider what skills or experiences are actually necessary. Some volunteer role descriptions include things like being personable and friendly, which can exclude people who are looking to volunteer to build their confidence. You may also consider whether volunteers really need any prerequisites to complete your roles, or if they can be trained and supported to do their tasks.

Offer a buddy system or group or family volunteer opportunities. If a person is worried, unsure or anxious about volunteering, you could offer to initially pair them up with an experienced volunteer who can support them. You could also offer group or family volunteering opportunities so that people can try out a new activity amongst the security of friends and family members. The buddy system can also be a great approach for supporting people who are volunteering to improve their English language skills.

Offer shorter shift times. Some people may not be able to stand for long periods of time, or may be living with conditions that cause fatigue. Think about if you could break up longer shifts into shorter periods, or adapt roles so volunteers can complete them whilst seated.

Photo Credit: Historic Environment Scotland.

Communication

The way organisations communicate - the words and images used, tone of voice, format of designs and channels chosen - affect whether they exclude or include a person or a group.

Design

How communications are designed can increase the accessibility of your information. In order to maximise the number of people who can understand your graphic design, consider the following:

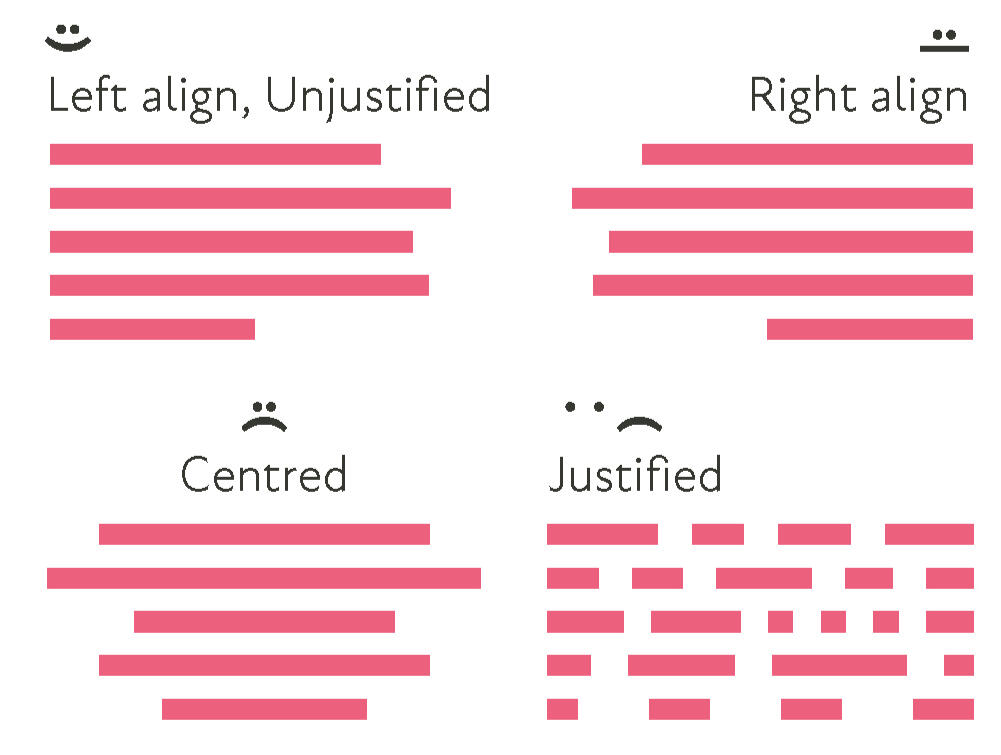

Left align your text.

In some languages, like English and Scots, sighted readers are used to reading from left to right, and from top to bottom. Left aligned text is therefore typically the easiest to read because it best follows these expected conventions.

Right align, centred, and justified text is harder to read because sighted readers have to work harder to find the start of each line, and have to process unexpected spacing in-between words.

Write in Sentence Case.

Writing full words in capital letters is harder to read, so capital letters should only be used for proper nouns and words at the beginning of sentences. If you would like to highlight or emphasise words, use bold or increase the size of the font.

This is an example of sentence case.

This Is An Example Of Initial Case.

This is an example of small caps.

THIS IS AN EXAMPLE OF UPPERCASE.

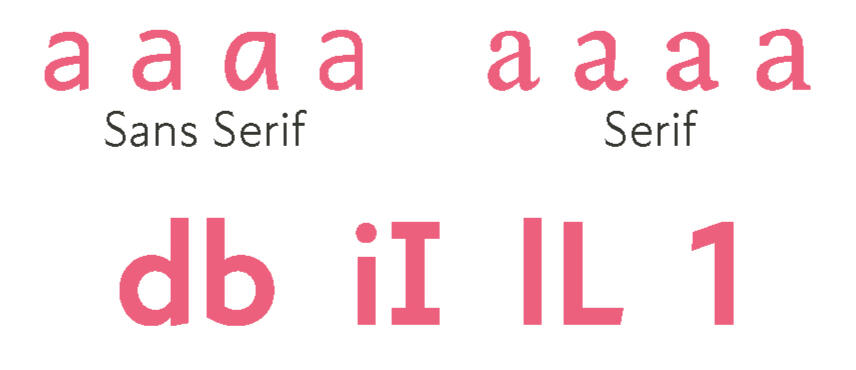

Use sans serif fonts.

San serif fonts (fonts without decorative lines or curls added to them) are generally easier to read than serif fonts.

Accessible fonts do not have mirrored lettering, meaning ‘d’ is not the mirror image of ‘b’. Accessible fonts should also have distinct characters for uppercase i, lowercase L and the number 1.

If your organisation’s brand guidelines include the use of a serif font, use a sans serif font for alternative versions of communications.

Free Sans Serif Examples

Roboto (Regular, Bold & Italic)

Atkinson Hyperlegible (Regular & Bold)

Open Sans (Regular, Bold & Italic)

All of these fonts are available for free for personal and commercial use from Google Fonts.

Use at least 12-point font size in printed media.

A point is the smallest unit of measurement in a font, and averages 0.358mm. Therefore, using 12pt should ensure text will be large enough to be comfortably read, regardless of font choice.

In digital texts, users should be able to zoom or reflow your content, so point size is less of a priority.

Use bold, avoid italics.

Italicised fonts contain exagerated shapes which can make them harder to read. Underlining text to emphasise it can be similarly disorientating. Slanted oblique fonts are often conflated with italics; while they’re less confusing, regular fonts are preferred.

Use bold sparingly

Overuse can make a piece of text harder to read, rather than highlight key information.

This is an example of text where the bold is used sparingly.

This is an example of text where the bold is used too much.

Replace italics with quotation marks.

Italics are a popular way to indicate the title of something or to signal a quote, but italicised text changes the weighting of the font and makes text harder to read.

As noted in this “Guide to Accessible Text”, quotation marks are preferable.

As noted in this Guide to Accessible Text, italicised text isn’t preferable.

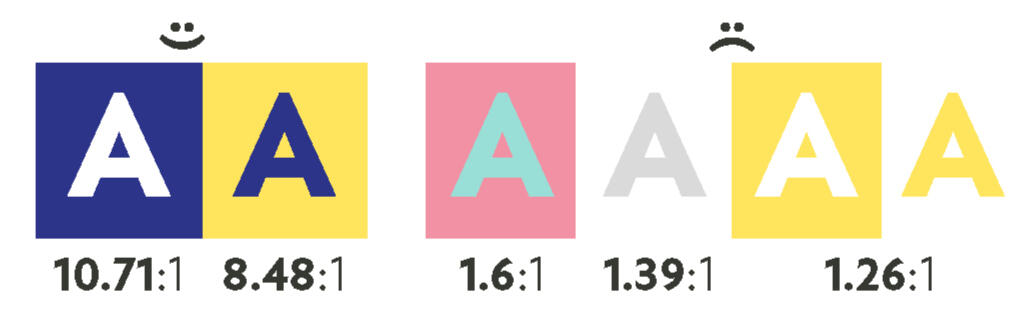

Use high contrasts.

Documents with a high level of colour contrast between background and foreground colours are easier to read. You can check the strength of your colour contrast with WebAIM’s Colour Contrast Checker.

WCAG level AAA guidelines recommend a contrast ratio of at least:

7:1 for normal text (e.g. body)

4.5:1 for large text (e.g. headings)

3:1 for graphics

Contrast levels aren’t everything! Consider other forms of legibility, like combinations of glaring colours.

Use images intentionally.

Because not everyone will be able to access the image in the same way, images should not be the sole way of communicating information. Images should illustrate key messages, not introduce new points. Images and graphics should portray a diverse range of people.

Photo Credit: Julie Howden.

Language and terminology

Using inclusive language increases the number of people you can communicate with. Below, we’ve outlined some general best practices of inclusive language.

For more specific guidance on terms relating to race, sex and gender, sexuality, class and disability, please see the glossary.

Use simple sentence structures. This means that sentences are concise and ideas are broken up into short paragraphs.

Use the active voice. This means that a sentence has a subject that acts upon its verb. For example, “I attended the Make Your Mark event” (active) rather than “The Make Your Mark event was attended by me” (passive).

Address readers directly by using ‘we’ and ‘you’. This language is approachable and encourages audiences to engage with you. Inclusive communications views communication as a partnership in which all people are equal, with equal amounts to give, share and learn from each other.

Avoid jargon, such as organisational acronyms and sector-specific words like ‘heritage.’ The Heritage Blueprint Report (Young Scot and National Trust for Scotland, 2017) found that while 34% of young people were interested in ‘history’, only 16% had an interest in ‘heritage’. You may consider replacing ‘heritage’ with ‘history’, ‘culture,’ ‘buildings,’ ‘places,’ ‘collections,’ ‘stories’ and other words as appropriate.

Materials in different languages

Many potential volunteers might not have English as a first language or might not be confident in their English language skills. To encourage people from these communities to apply, you could have a few key phrases or materials translated into different languages.

Deciding what languages to offer materials in can be tricky, as demographic data often groups many ethnicities with different cultures and languages together. To help you map the languages spoken by people in your area, you could:

Check what countries or languages are represented by university societies.

Liaise with libraries, councils and council-run facilities.

Search for local Facebook groups for different nationalities and languages.

Research local restaurants or shops that offer international food.

Case Study: Supporting multilingual volunteers

For Doors Open Days 2019, the Scottish Civic Trust engaged volunteers to deliver Polish and Farsi tours of Glasgow City Chambers.

In this case study on supporting multilingual volunteers, read about how they partnered with Scottish Refugee Council, Refugee Survival Trust, Sikorski Society and Glendale Women’s Cafe to recruit refugee and migrant volunteers.

Alternative formats

In addition to offering materials in different languages, offering other alternative formats can make your volunteer programme more accessible for people with learning, hearing or visual disabilities.You could create:

Easy read versions, which break down complex information into shorter text and support the meaning of the text with the use of simple images or icons. Easy read versions are accessible to people with a learning disability and can also be accessible to those whose first language is not English or who have a lower reading level.

Large print versions, which are generally 16 to 18 point font size.

Braille versions. There are around 12,000 Braille users in the UK, and a few English Braille codes currently in use. If you choose to create Braille materials for audiences, you can post these materials for free via the Royal Mail under the Articles for the Blind scheme.

Video versions. Short videos (under 2 minutes) which can easily be shared across social media may help to reach new groups and communities. Where possible, having the video in 2-3 major languages spoken in Scotland will help to increase reach. Ensure to caption videos to increase accessibility, and double check that any auto-generated captions are accurate.

Audio versions. Community radio stations continue to be a vital source of connection for many groups. Consider short ads or features on local community radio stations.

British Sign Language (BSL) versions. 1 in 6 of the UK population experience deafness. Engaging with organisations such as Contact Scotland BSL will help to ensure your organisation is confident in supporting a broader range of volunteers.

Case Study: Engaging

with non-screen users

To address the digital divide and engage with people who experience barriers in accessing and using screen technology, the National Galleries of Scotland offers a variety of non-screen-based engagement options.

In this case study on engaging with non-screen users, read about how they use teleconferencing, postcards, letters and more.

Photo Credit: Scottish Civic Trust.

Supporting Volunteers

Once volunteers are recruited, it is essential that volunteer organisers take steps to support them and ensure that they have a positive experience. Volunteer organisers should consider:

Creating a clear induction process. This should include a volunteer agreement and an introduction to policies (see section 4).Identifying a clear point of contact and communication. This will ensure that volunteers know who they can contact with questions and concerns.Organising regular check-ins. This will provide volunteers with opportunities to discuss the experience and how it could grow and/or be improved.Hosting annual surveys, exit surveys and focus groups. This will capture honest reflections and responses from volunteers about their experiences.Providing information on skills development and employment support. This will ensure that volunteering is mutually beneficial for the organisation and volunteer, and may include developing training pathways and shadowing opportunities, offering feedback on CVs, hosting mock interviews and providing references.Signposting to other specialist organisations that can support people in various ways. Every volunteer is unique, with their own backgrounds, experiences and abilities, and facing their own set of challenges. In the current cost of living crisis, many people are struggling to make ends meet, which can negatively impact their mental health. Whilst volunteer organisers can support people within the boundaries of their role, there may be times where it is helpful and appropriate to support volunteers in accessing other specialist organisations and resources, such as financial support and debt management, health and wellbeing support, domestic abuse support, mental health support and more.Thanking volunteers and recognising their efforts. This will ensure that volunteers feel valued for their contributions. Volunteer Scotland provides guidance on recognising and valuing your volunteers.

Case study: Supporting volunteer development

The National Mining Museum, National Museums Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland and The David Livingstone Birthplace all take different approaches to volunteer development.In this case study on supporting volunteer development, learn about how they empower volunteers to make tasks their own, highlight to volunteers how they can support them and create basic development plans.

Case study: Creating pathways to volunteering for people accessing mental health support.

St Andrews Botanic Garden has recently implemented their “Planting For Your Piece” project to much success. In this case study on how to set up supported volunteer programmes for people accessing mental health support, learn about how they collaborated with local mental health organisations to recruit and support new volunteers.

Illustration Credit: Saffron Russel.

Budgeting for inclusion

Many people face economic barriers to volunteering, including travel expenses, childcare costs, food costs and a lack of free time. When applying for funding, volunteer organisers should budget for these factors to enable more people to volunteer.Especially in the current economic climate, volunteer-involving organisations should pay travel costs for volunteers as a minimum, and all other out-of-pocket expenses where they are able. Volunteer Scotland has produced further guidance on supporting volunteers during the cost of living crisis.In terms of the legalities of expenses, you must be sure you only pay the exact amount of expenses that a volunteer has incurred. You must have receipts and never pay out a fixed amount. If a volunteer is given a regular, fixed sum, they can technically be considered an employee, would need to be paid the UK minimum wage and could be taxed on that income. Paying volunteers a fixed amount can also put people receiving UK welfare benefits at risk of losing them. Volunteer Wiki has outlined additional detail about the rules around paying expenses.

Case study: Volunteering and UK welfare benefits. Experts from Volunteer Glasgow cover everything that voluntary organisations need to know about how to support people receiving UK welfare benefits to volunteer, including a few practice examples.

Below is a sample budget for costs associated with an inclusive volunteer programme.

Budget 1: Travel costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Bus | Return or all day bus ticket, up to £6 |

| Car or van | 45p / mile. 1 |

| Motorcycle | 24p / mile. 1 |

| Bicycle | 20p / mile. 1 |

| Passengers | 5p / passenger / mile for carrying fellow volunteers in a car or van. 1 |

| Taxi | approximately £50 / return trip |

Budget 2: Childcare costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Organise a mobile crèche | Get a quote from Flexible Childcare Services Scotland. |

| Support volunteers to access early years and childcare support | The Scottish Government offers a range of support for early years and childcare. Helping volunteers access this support could be an in-kind contribution from staff. |

| Develop family volunteering opportunities | In-kind contribution from staff |

Budget 3: Disclosure costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Disclosures for volunteers working with children or protected adults | Volunteer Scotland provides free disclosure checks for voluntary organisations. |

Budget 4: Food costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| 5+ hours volunteering / day | Up to £5. 1 |

| 10+ hours volunteering / day | Up to £10. 1 |

Budget 5: Thanking volunteer for their time

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Review volunteers’ CVs & host practice interviews | In-kind contribution from staff |

| Organise shadowing experiences | In-kind contribution from staff |

| Annual thank you event | £20 - £40 / volunteer. Volunteer organisers could organise catering and celebrate with volunteers on-site, or partner with another organisation to organise a volunteer day out. |

Budget 6: Communication costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| British Sign Language Interpreters | £100 / hour, £155 / half day, £310 / full day (Nubsli, 2024). |

| Language Interpreters | £40 - 150 / hour, £150 - £500 / half day, £250 - £700 full day (Translation & Interpreting, 2022). |

Budget 7: Other costs depending on role or sector

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Training required by volunteers | Varies. |

| Equipment or clothing costs required by volunteers | Varies. |

1 As per rates from HMRC.

2 At the time of writing (January 2025), changes are being made to the current disclosure system and funding. Please check Volunteer Scotland Disclosure Services for the most up to date information.

Photo Credit: David Livingstone Birthplace.

Inclusion checklist

Please use this checklist to understand the barriers to inclusion in your organisation. This can be used to develop an inclusive volunteering plan (see Section 8). Which of the below practices and facilities can your organisation offer to volunteers?

1. Economic

Travel expenses can be paid up-front.

Travel expenses can be reimbursed.

Childcare can be provided.

Equipment costs are covered.

Disclosure is required, but the cost is covered and previous convictions do not necessarily disqualify applicants.

Volunteer expenses will not compromise UK state benefits.

Volunteers are thanked for their time via social events.

Volunteers can be reimbursed for up to £5 of food costs per 5 hours of volunteering.

2. Social & Cultural

Venue staff have undergone equality, diversity and inclusion training.

Volunteers of all skill sets and backgrounds are encouraged to apply to share their unique expertise, and previous experience or a degree is not required.

Volunteer taster sessions are available.

Opportunities to shadow an

existing volunteer to learn about the role are available.

There are multiple ways to apply: application form, phone call, voice note, video, etc.

Volunteer managers are happy to chat with volunteers about their needs and adapt roles to suit them.

Volunteer recruitment materials represent a diverse range of people.

Volunteer recruitment materials are available in a range of languages.

The organisation has an equality, diversity and inclusion strategy and is committed to welcoming people of all backgrounds, experiences, identities, abilities and needs.

3a. Physical: Entering and Accessing Venues and Sites

Nearby accessible public transport.

Disabled parking on-site.

Free parking nearby.

Bike rack on-site.

Wheelchair accessible ramps,

toilets and lifts.

Seating available throughout

Access rider can be included with submission.

3b. Physical: Engaging at Venues and Sites

Hearing loop.

Gender neutral toilets.

Gender neutral baby changing facilities.

Provides free period products.

Available quiet spaces.

Drinking water refill stations.

Service dogs fitted with a suitable harness or on a lead are allowed in the venue.

Water available for service dogs.

The site offers interpretation in languages besides English.

BSL interpretation can be provided

A visual and sensory guide is available with information about what to expect at the venue.

Large print and Braille options available.

Magnifying glasses are available for use.

Volunteers can specify if they’d like to come in at quieter times.

If you want more detailed feedback on the accessibility of your volunteer programme, you can partner with a local organisation that engages with marginalised people to arrange an accessibility audit with their members. This may consist of their members visiting your venue, reviewing policies or role descriptions and/or participating in a volunteer taster session and giving you feedback on how to be more accessible or inclusive. Consider contacting potential partner organisations for quotes and developing a budget for this type of expert work.

7. Benchmarking and Tracking the Benefits of Inclusive Volunteering

Inclusive volunteering has benefits for individuals, organisations and societies. This section of the toolkit outlines the social justice and economic case for inclusive volunteering, and why collecting data on your volunteer programme is a critical tool for change.

Why inclusion is a social justice and economic issue

The Centre of Economics and Business Research’s recent research into the value of volunteering (2023) showed that volunteering makes a major contribution to the economy and can be considered a vital part of Scotland’s Inclusive Growth Strategy:

“The Scottish Government defines inclusive growth as ‘growth that combines increased prosperity with greater equity; that creates opportunities for all; and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity fairly" (Scottish Government, 2015).”

What does it mean to fairly distribute the dividends of volunteering opportunities in Scotland? The cost of living crisis has had an impact on volunteering through cuts to funding and giving, and constrained time or personal circumstances for individual volunteers.

Combined with an increase in the need for volunteers, this produces a complex challenge for the sector:

How can we ensure the benefits of being a volunteer are equally distributed in society when it relies on a high volume of unpaid labour?

How do we support individuals, groups, and communities who have additional barriers to participating in volunteering?

What can volunteering offer individuals and society?

By volunteering, people can:

Meet people and develop new social networks.

Develop skills and experience.

Build their CV.

Gain knowledge.

Increase confidence and self-esteem.

Improve wellbeing.

Become more involved in their community and built a greater sense of belonging.

Involving a wider range of volunteers enables volunteer organisations to:

Value and celebrate the skills and experiences of Scotland’s diverse society.

Adhere to funding requirements for inclusion and diversity.

Reflect the diversity of Scotland’s communities.

Expand engagement with volunteering.

Develop volunteer organisers’ skills around inclusive engagement.

Although volunteering has many documented benefits, it has not previously been accessible to, and inclusive of, everyone, thereby limiting its positive impact. Involving a more diverse range of people in volunteering would:

Enable everyone to have the opportunity to experience the social, physical and health benefits of volunteering, thereby reducing exclusion.

Ensure that activities undertaken by voluntary organisations meet the needs of Scotland’s diverse communities.

Inclusive volunteering at your organisation

How does your organisation recruit, retain, and value volunteers? Consider each in turn.

Is there anything about diversity and inclusion that is a barrier for your organisation (either skills, knowledge about terminology or experience of practice)?

Is diversity and inclusion important to your volunteering organisation? If so, how does this work in practice?

Are there any communities you feel are ‘missing’ from your volunteering organisation? Why do you think that is?

Where would you place your organisation in its journey to be more diverse and inclusive:

1. Early work?

2. Some initiatives are underway?

3. Well developed?

Are there other organisations who you think you could learn from or share your best practice with?

Illustration Credit: Saffron Russell

Data and benchmarking: why does it matter?

Collecting data from volunteers about their backgrounds is a powerful tool that can enable you to create effective inclusive volunteering plans.

Data can help identify trends and evidence, as well as contradict or confirm anecdotal knowledge you have about your organisation. Organisations should never assume anything about someone’s identity - collecting personal data from volunteers themselves ensures that you have an accurate picture of your volunteer programme.Basic data gathering on protected characteristics can help an organisation to benchmark where they are, and how they compare against other organisations. The same data can be used to identify goals for the future (e.g. creating a plan to engage more disabled volunteers and support their ongoing participation). This section outlines a range of data that can be tracked about volunteers, along with how that data can be sensitively stored and used.While there is some data on volunteering demographics in Scotland (see section 2), there are gaps in the data picture.If all organisations gathered more basic data about volunteering, we could:

Inform a more detailed national picture about who volunteers and why.

Evidence barriers to volunteering for marginalised and underrepresented groups.

Demonstrate how the social, cultural, and economic benefits of volunteering can be distributed across Scottish society.

Combining qualitative (non-numeric information about emotions and perceptions) and quantitative (numeric information such as statistics) data can help to gather a range of evidence. Each type of data serves a key and different purpose, and are most effective when used together.Quantitative data is useful for creating concrete goals (e.g. we want to increase the number of disabled volunteers by 30% in three years).Qualitative data can be particularly useful when you’re trying to understand the reason for more complex barriers (e.g. why people don’t feel included). Qualitative data is often best collected through surveys or focus groups (see section 6). Quantitative data is useful for creating concrete goals (e.g. we want to increase the number of disabled volunteers by 30% in three years).The types of questions you ask should be shaped by your organisation’s objectives as well as funders’ requirements. For example, you may want to include questions like:

1. What are your reasons for volunteering with us?

Meet new people

Develop skills and experience

Build my CV

Gain knowledge

Interest in the topic / sector

Increase confidence and self-esteem

Give back to the community

Make a difference

Improve my wellbeing

(Write in)

2. How does volunteering with us make you feel?

3. What do you like about volunteering with us?

4. What could we do to improve your volunteering experience?

5. How else could we support you to get the most out of your volunteer experience? Are there things we could do to make it more accessible or easier for you to enjoy?

6. How satisfied are you with your volunteering experience?

Not very satisfied

Not satisfied

Neutral

Satisfied

Very satisfied

7. My volunteering experience has (check all that apply):

Helped me with developing skills

Increased my confidence

Improved my health or wellbeing

Made me want to look at training or work opportunities in the sector

(Write in)

8. How else has volunteering impacted you (if applicable)?

9. Is there anything else you want to say about your volunteer experience?

Vision for Volunteering has created a free resource pack to support organisations to use ripple impact mapping, a participatory and interactive data capture method, to better understand the ‘ripples’ of impact that are hard to measure by traditional methods or that don’t happen immediately.

Equalities monitoring

Equalities monitoring involves the collection of information, or data, about volunteers. Many organisations choose to monitor ‘protected characteristics’ as identified in The Equality Act (2010):

Age

Disability

Gender reassignment

Marriage and civil partnership

Pregnancy and maternity

Race

Religion or belief

Sex

Sexual orientation

A template Equalities Monitoring form is available from Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (see appendix).

Collecting data about socio-economic backgrounds and social mobility

Although work on inclusion often focuses on protected characteristics, socio-economic background is a key underpinning condition for exclusion, discrimination and inequality.

For an insight into tackling socio-economic inequalities, please see the Social Mobility Commission’s Socio-economic Diversity and Inclusion toolkit, which is based on case studies from the creative industries.

Data storage, ethics and accountability

When collecting, storing and analysing personal data about volunteers, it is important to comply with legal requirements to protect people’s privacy.

Not everyone will feel comfortable providing data about themselves. It’s important to explain the reasons why you are asking for the data, how you will keep it safe and how you will use it. Here is a template statement to use when collecting equalities data:

Equality and inclusion are at the heart of our work. We collect information about volunteers’ backgrounds and identities to help us ensure that our volunteer programme reflects the diversity of Scotland’s people.Supplying personal data to us is voluntary. The information you supply is confidential and anonymous. It will not be linked to your application and is used for monitoring and reporting purposes only.

It is important to comply with the Data Protection Act (2018) when processing personal data about individuals. Under this law, you must ensure:

The data is used for a clear, specific purpose.

You collect and use the minimum amount of data required to fulfil your purpose.

The data is kept for no longer than is necessary.

You provide clear instructions and a point of contact for people to get in touch if they want you to remove their data from your records.

The data is stored securely.

SCVO provides detailed guidance on data protection, and the Information Commissioner’s Office has a data protection self-assessment toolkit. If you are a large organisation and will be collecting a high volume of data, Volunteer Scotland provides guidance about responsible research and ethics.

Volunteer equalities monitoring

What data do you collect and are you confident you are complying with data storage requirements?

How do you use data in organisational decision making and why? Does social inclusion feature as a category to analyse?

Illustration Credit: Saffron Russel.

Quality standards

Working within your organisation to achieve a recognised quality standard provides a framework that can help you evaluate and improve your volunteer programme.[Volunteer Scotland’s Volunteer Charter]((https://www.volunteerscotland.net/volunteer-practice/quality-standards/volunteer-charter/) is an initial standard for volunteer-involving organisations to sign up to. It sets out ten principles which help to underpin good relations within a volunteering environment. It is open to any group or organisation from any sector that involves volunteers.Once your organisation signs up to the Volunteer Charter, you may consider working towards a further quality standard:

Volunteer Friendly Award is a Scotland quality standard for small to medium volunteer programmes, including small community and mutual aid groups. Requirements are set at an achievable level for each volunteer programme, covering five foundation quality standards and 18 key volunteer practices.

Investing in Volunteers (IiV) is a UK quality standard for medium to large volunteer programmes. It aims to improve the quality of the volunteering experience and ensure organisations acknowledge the contribution of volunteers. The IiV process includes an evaluation of your volunteer programme, with tailored support for how to develop a more inclusive approach.

By achieving a quality standard, you’ll be part of a growing community of peers focused on quality volunteer practice.

8. Developing an Inclusive Volunteering Plan

An Inclusive Volunteering Plan should set out an evidence-based, current picture of involvement across an organisation of marginalised people; highlight priority areas for development in inclusion; and set out plans and objectives for changes. This section of the toolkit supports you to develop your own Inclusive Volunteering Plan.

Process

1. Assess: Based on the toolkit, what are your organisation’s priority areas for development in inclusion (e.g. recruitment)? Identify 2-3 priority areas.

2. Plan and consult: What are your plans for positive changes? How did you develop these plans? Have you consulted with volunteers and relevant stakeholders? How will you measure or track positive change? Will this be through qualitative or quantitative data?

3. Pilot interventions: Test your plans in a limited-limited exercise (e.g. 3 months).

4. Evaluate: Did the interventions work? How has this been evidenced?

5. Reflect: Capture the learning from the exercise (including what didn’t work) and revisit your priority areas. Has there been positive change for inclusion?

Case study: Creating an inclusive volunteer philosophy. Creating a volunteer philosophy can help you define why your organisation involves volunteers and how you involve volunteers in carrying out your mission. In this case study on creating an inclusive volunteer philosophy, HMS Unicorn explains why and how they created their “WaveMakers” volunteering programme on a limited budget to make a real, life-changing difference to a diverse range of local residents.

Planning for inclusive volunteering

How inclusive do you think your organisation is? On a scale of 1-10, how confident are you that the organisation has an inclusive approach to volunteering -

(1 least confident, 10 most confident)?

Do you have the policies and structures in place to support people? Do you have any policies centred on developing an inclusive approach? If so, do they have an inclusive volunteering plan? Based on this toolkit, will you make any changes?

What can your organisation change in the short and medium term to improve inclusion? If you do not have policies centred on developing an inclusive approach to volunteering, design an inclusive volunteering plan based on:

3 things you can change or implement now, and 3 things you would like to change or implement in the medium term.

How can your organisation measure and benchmark inclusion more effectively? What kind of data do you need and how will you collect, store, and analyse it for evidence-based decision making?

Reflective Worksheet

To help you start organising your thoughts, we’ve collaborated with Volunteer Scotland’s Volunteering Action Plan to create a reflection worksheet.You can download a form fillable worksheet, or copy the questions below and fill them out using whatever word processor or mind-mapping app that suits your process:

Barriers to volunteering with my organisation

What factors, practices or policies may be preventing people from volunteering with us?

External Barriers

Internal Barriers

Who is affected?

Actions to take to remove barriers

What changes can we make to enable more people to volunteer? What resources, funding or new relationships would I need to achieve this?

Short Term

Medium Term

Long Term

Potential collaborators

Which allies, partners or networks could I draw on or work with?

Resources to investigate

What helpful guides, templates and toolkits are available to support me in making changes? For example:

How changes and success will be measured

For example: equalities data, surveys on volunteer experience, KPIs to hit, etc.

Glossary

Diversity